The Learning Style Myth

You’ve probably heard that when it comes to learning, we have a dominant sensory modality, or “learning style.”

By the time we get to college, someone has told us that we are either “visual,” “auditory,” or “kinesthetic” learners and that we learn best in our preferred style.

According to the American Psychological Association, 90%+of teachers believe students learn better if taught in their predominant learning style.

I was one of those teachers.

I spent tons of time and effort trying to identify the learning styles of my students. I used a version of the VARK questionnaire, for example, to sort my students into learning style buckets. Then, I created different learning experiences for every group, tailoring my instruction to each student’s learning style.

This took a lot of work, but “it was worth it,” I thought. “Anything to help them learn.”

I was wrong.

While the idea of “learning styles” sounds rational and appealing, numerous studies have debunked this theory.

Here are 3 things I learned and 4 tips to avoid The Learning Style Myth:

The Learning Style Myth

1. We don’t have one “learning style”

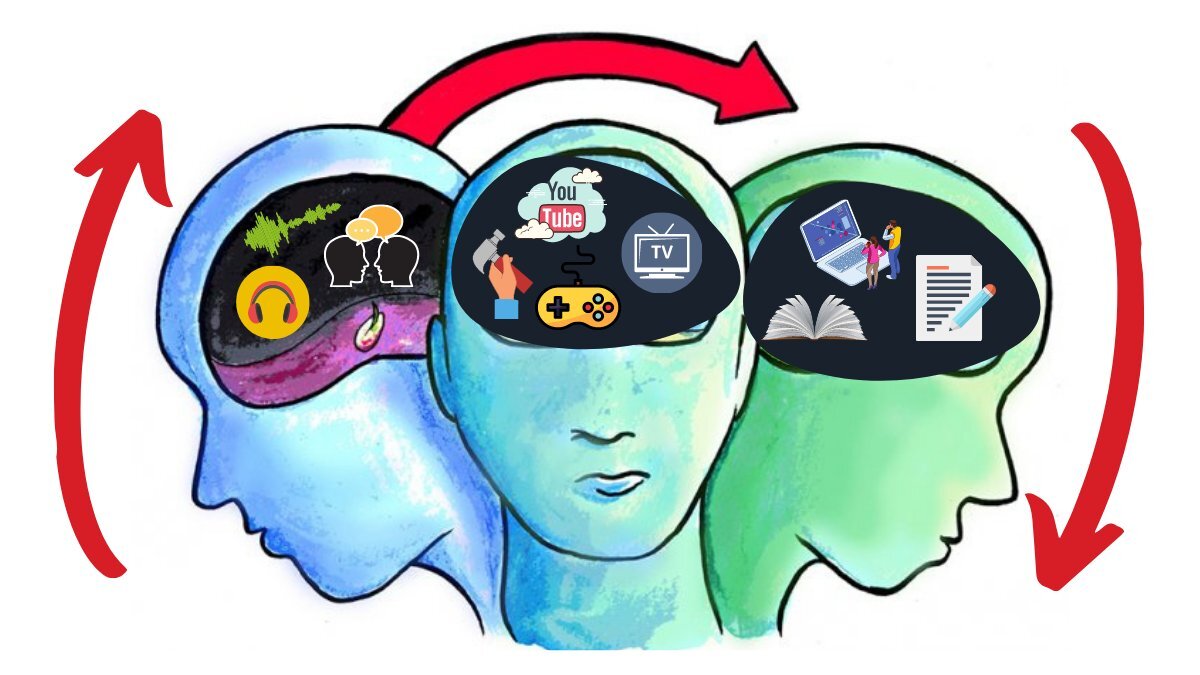

The idea that we have a dominant sensory modality is a lie. Visual, auditory, and motor input modalities in the brain are interconnected, and this interconnectedness is what helps us process information. In other words, when we are learning, we engage more than one sense at a time.

For example, we may best learn how to cook by watching a YouTube video, but this does not mean we are “visual learners.” By watching a cooking video, we are actually engaging sight, sound, and probably touch.

Here’s a study that shows how our brain is more efficient when it processes information through multiple senses at the same time.

2. Tailoring instruction to match students’ “learning styles” does not lead to better learning outcomes

Countless studies have demonstrated that catering to differences in students' preferred learning style does not improve learning outcomes.

In this study, for example, hundreds of students took the VARK questionnaire to determine their learning style. The survey then asked them to prepare on a topic, using strategies that were supposed to match their learning style.

The study found that a) most students did not prepare in ways that seemed to reflect their learning style and b) the few who did, didn’t do any better on their assessment.

Another example is this research study that suggests that what leads to better learning outcomes is the opportunity to engage in as many sensory modalities as possible.

Here are two write-ups by Anne-Laure Le Cunff, an entrepreneur and a neuroscience student I admire, that sparked my thinking on this idea: Learning How To Learn and Neuromyths: debunking the misconceptions about our brains.

3. Learning styles encourage a fixed mindset

There is no benefit in classifying ourselves as visual, verbal, or kinesthetic learners. We can learn using any and all sensory modalities.

We don’t help kids when we “label” or “classify” them around a particular learning style. A kid who believes they have a dominant style could lean into a fixed mindset. By promoting learning styles, we limit students with self-fulfilling prophecies despite our good intentions.

Sometimes by trying to celebrate kids' individuality, we could swing the pendulum too far and end up putting kids into boxes again. Back when I was a teacher, I blindly adopted the idea of learning styles without really questioning its validity or evaluating the research myself. The result? I fell prey to a popular learning myth about the brain and its functioning.

How to Avoid The Learning Style Myth

Clarify to your kids that they don’t have a learning style. They have learning preferences, or predispositions to perceive and process information using a combination of sensory modalities!

Emphasize that our learning preferences are not fixed. They may change over time and depending on the situation. One day we may be inclined to learn about history by watching a documentary, and another day we may want to read a blog post on it.

Remind kids they have a toolbox of ways to think and learn. When they want to learn something new, encourage them to ask themselves “which mental tool (or tools!) would work best for this topic or scenario?”

Give kids the opportunity to engage in as many sensory modalities as possible. In this day and age there are countless ways we can learn about a topic: Youtube, books, podcasts, documentaries, online courses, bootcamps, online articles, or in-person study groups, to name a few. Have them choose a topic and learn about it in three different ways. Help them reflect on what they notice.

I explore ideas like this in Fab Fridays, my newsletter on childhood education and new ways to learn.

Subscribe below!